PALLIATIVE CARE: is the care for people of all ages with a life-limiting or life-threatening condition which aims to;

- Optimise an individual’s quality of life until death by addressing the person’s physical, psychosocial, spiritual and cultural needs.

- Support the individual’s family, whanau, and other caregivers where needed, through the illness and after death.

Palliative care is provided according to an individual’s need, and may be suitable whether death is days, weeks, months or occasionally even years away. It may be suitable sometimes when treatments are being given aimed at improving quantity of life.

It should be available wherever the person may be located.

It should be provided by all health care professionals, supported where necessary, by specialist palliative care services.

Palliative care should be provided in such a way as to meet the unique needs of individuals from particular communities or groups. This includes but is not limited to: Maori, children and young people, immigrants, those with intellectual disability, refugees, prisoners, the homeless and those in isolated communities (Palliative Care Subcommittee NZ Cancer Treatment working Party 2007).

Palliative Care approach: is an approach to care which embraces the definition of palliative care.

It incorporates a positive and open attitude toward death and dying by all service providers working with the person and their family, and respects the wishes of the person in relation to their treatment and care.

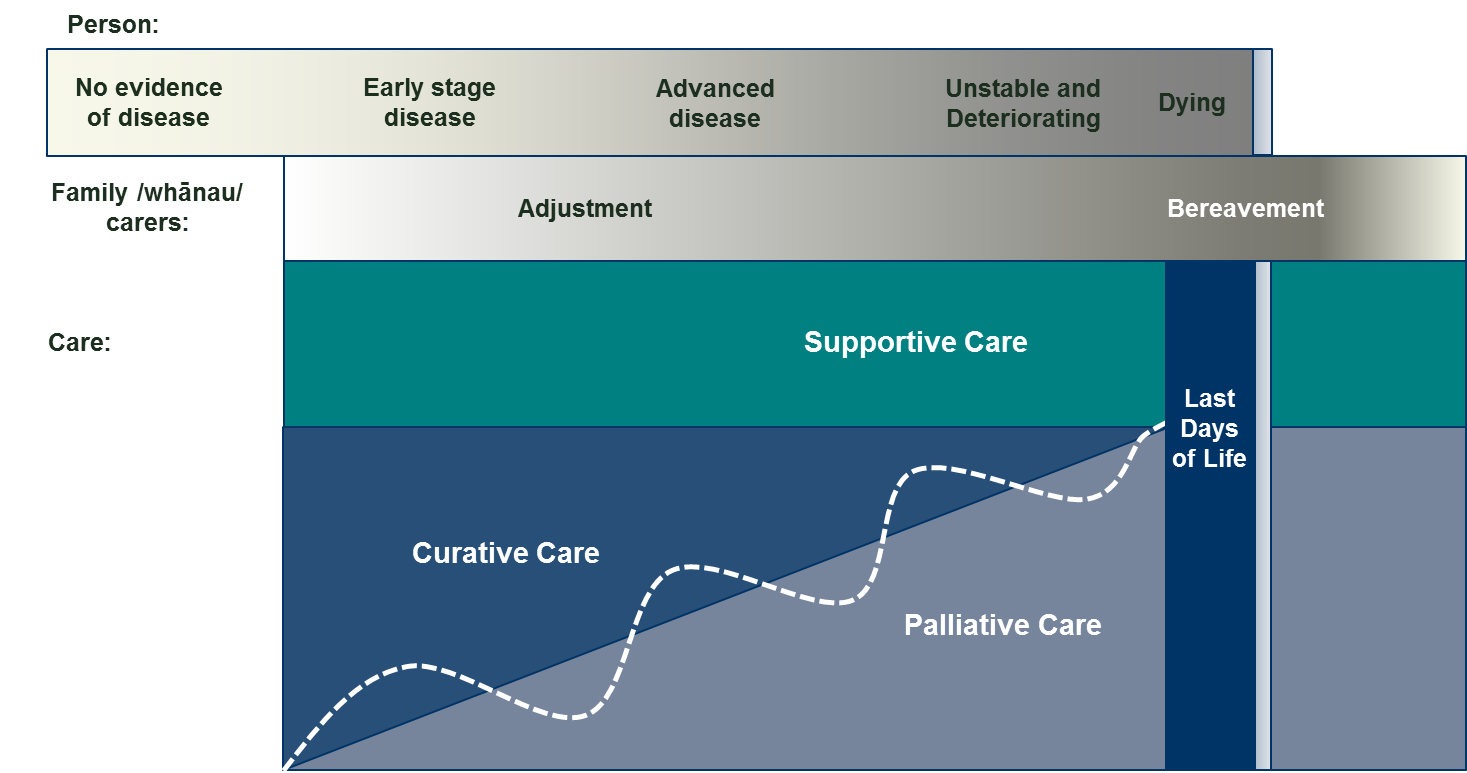

Figure 1: Adjustment, support and palliative care for adults

Specialist Palliative Care: is palliative care provided by those who have undergone specific training and/or accreditation in palliative care/medicine, working in the context of an expert interdisciplinary team of palliative care health professionals.

Specialist palliative care may be provided by hospice or hospital-based palliative care services where people have access to at least medical and nursing palliative care specialists (Palliative Care Subcommittee NZ Cancer Treatment Working Party 2007).

Specialist palliative care is delivered in two key ways:

- Directly – to provide direct management and support of the person and family/whānau where more complex palliative care need exceeds the resources of the primary provider. Specialist palliative care involvement with any person and the family/whānau can be continuous or episodic depending on the changing need. Complex need in this context is defined as a level of need that exceeds the resources of the primary team – this may be in any of the domains of care – physical, psychological or spiritual.

- Indirectly – to provide advice, support, education and training for other health professionals and volunteers to support the primary provision of palliative care.

Primary Palliative Care (Non specialist palliative care): is provided by all individuals and organisations who deliver palliative care as a component of their service, and who are not part of a specialist palliative care team.

Primary palliative care is provided for those affected by a life-limiting or life-threatening condition as an integral part of standard clinical practice by any healthcare professional.

In the context of end of life care, a primary palliative care provider is the principal medical, nursing or allied health professional who undertakes an ongoing role in the care of people with a life-limiting or life-threatening condition. A primary palliative care provider may have a broad health focus or be specialised in a particular field of medicine. It is provided in the community by general practice teams, Māori health providers, allied health teams, district nurses, and residential care staff etc. It is provided in hospitals by general ward staff, as well as disease specific teams – for instance oncology, respiratory, renal and cardiac teams.

Primary palliative care providers assess and refer people to specialist palliative care services when the needs of the person exceed the capability of the service.

Quality care at the end of life is realised when strong networks exist between specialist palliative care providers, primary palliative care providers, support care providers and the community – working together to meet the needs of the person and family/whānau.

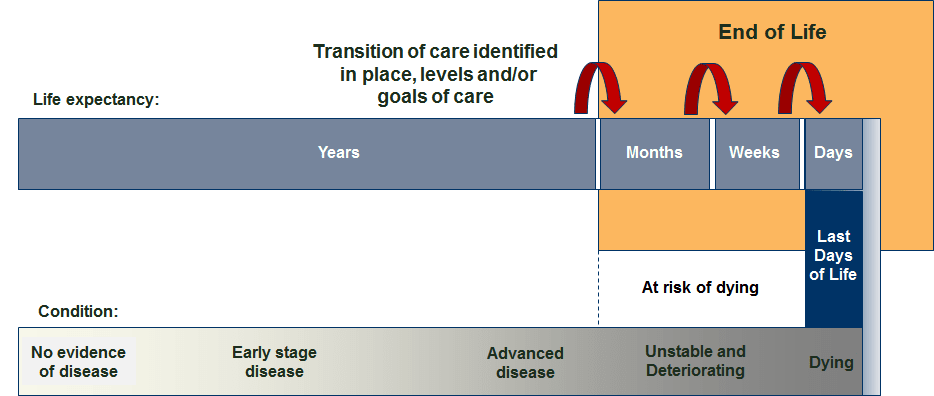

End of Life: is that period of time prior to death but the duration can never be precisely defined in advance (National Gold Standards Framework Centre 2011).

Recognising and identifying those people who are at risk of dying at some point in the year ahead enables the health and social systems to respond to the deteriorating person and their families/whānau/carers in a holistic and comprehensive way.

Although prognostication is inherently difficult, being better able to predict when people are reaching the end of life phase, whatever their diagnosis, makes it more likely that they receive well-coordinated, high quality care. This is more about the health care system meeting needs than giving defined timescales. The focus is on anticipating the needs of the person and families/whānau/carers so that the right care can be provided at the right time. This is more important than working out the exact time remaining and leads to better proactive care in alignment with preferences.

The end of life period is triggered by a transition in the place of care, levels of care and/or goals of care. The major transition to the end of life period is in changing the focus on the person from curative and restorative care, which aims to extend the quantity of life, to palliative care which aims to improve the quality of life.

Figure 1: End of life and last days of life

Last Days of Life: is the period when a person is dying. It is the period of time when death is imminent and may be measured in hours or days (Palliative Care Council 2015).

ALLOW NATURAL DEATH (AND): is an instruction written for other healthcare providers that allows a natural course of events to occur in an acute care setting (Paediatric Palliative Care Coalition 2015). The term Allow Natural Death may be used as an alternative to Do Not Attempt Cardio-Pulmonary Resuscitation (DNACPR), or Do Not Resuscitate (DNR).

It is an active, positive position embodying the hope that dying will occur peacefully and naturally as possible, surrounded by loved ones. Allow Natural Death codifies the spirit of ongoing communication between the person and legal decision-maker(s) and the health care team. Its completion should not be viewed as an end in itself, but rather as a tool to document preferences while facilitating further advanced care planning (Paediatric Palliative Care Coalition 2015).

A decision to allow natural death does not indicate a withdrawal of care, although it may include withholding or discontinuing resuscitation, artificial feedings, fluids, and other measures that would prolong a natural death. In addition to agreed interventions, the person will continue to receive:

- prompt assessment and management of pain and other distressing symptoms

- other comfort measures including emotional, cultural and spiritual support

- privacy and respect for the dignity and humanity of the person and their family/whānau

- management of hydration and nutrition needs as appropriate

- oral and body hygiene.

Reference

Ministry of Health. 2015. New Zealand Palliative Care Glossary. Wellington: Ministry of Health.